PENSIVE SPACE

by Wayne Baerwaldt

Essay for the catalof of the exhibition at the Moose Jaw Museum and art Gallery, 2011

I.

In how many ways are pictures usually observed? It’s accurate to say that we observe pictures in as many ways as there are ways for individual dispositions to follow their own idiosyncratic likings and dislikings. We might observe pictures or images in an offhan manner or impulsively. Supplementary historical facts, critique, personal politics and emotional nuances may seduce us and cause a conceptual shift in perspective.

As an artist who carefully constructs her photographic pictures to elude definitive and prescriptive readings, Gabriela García-Luna aims to open doors to an aesthetic that questions commonly perceived realities. She suggests we observe her pictures with fewer, different or no expectations of knowing anything with any certainty and that another, more elusive quality is more revealing. In the process of compiling her observations of the commonplace (urban-rural landscapes, ancient buildings, wallpaper, etc.) from various parts of the world, she hints at revealing the unseen in her images. She accomplishes this, in part, by subtly manipulating the quality of light/colouration of her surfaces. To state this is, of course, to oversimplify a complex process that re-examines both the ordinary and aesthetic elements within an evolving photographic language. García-Luna has established a particular neutrality to her vision as both photographer and observer to better her “exploration of new territories, Canada, India and elsewhere, taking note of in-between things or something that can’t be grasped, something not said, nor important.”1

Like other artists, García-Luna’s patient investigation resembles that of a pathfinder searching for personal clarity in image or form-making, with many attempts to circumnavigate and rise above current aesthetic likes and dislikes to establish some kind of dispassionate judgment. There is a consistency in her search. Omnipresent is a luministic realism or light effect that enhances the recording of the physical aspects of a claim to reality. By controlling the luministic qualities in each photograph, she attains a transformation of the physical appearance of her subjects with a freedom of imagination, conceiving her subjects, rather, as “a state of mind.” Her manipulated images quietly and consistently over time challenge us as observers with an interchange of concrete and abstract images that have no absolute values. She mixes the two approaches to image making with resolved aplomb. It is not important that meaning be attached to her pictures so as to offer a literal translation.

For example, On the Skin of My Father, 2007, a large-scale photograph on light-weight fabric appears to represent a highly intimate portrait of García-Luna’s now deceased father from the sole perspective of a close-up of the epidermis of his forearm. The realism of the depiction suggests a calm moment of reflection on her father’s spirit while also visually confirming his enduring presence. García-Luna does not, however, aim to inspire pity for the deceased nor adoration for a revered family member. How is this neutral yet eloquent observation on the reality of the life and death cycle to be interpreted? Meaning is nuanced in several ways. The lightness of form and abstract composition translates an unqualified level of sympathy, devotion and love. The presentation format of the large-scale photograph is uncomplicated: a patterned image of skin on sheer fabric, hung informally from a wooden doweling. The simple presentation is about rest and the freedom found in a life passing, its import carried inside the viewer. A similar, engaging nuance is adopted in more recent works. New Territories, 2011 is a series of colour photographs of fragmented layers of patterned and shredded wallpaper being removed from an old home. It is a meditation on time and the ability of a damaged decorative surface to create an uncanny visual equivalent of a collaged mountain landscape. It is a deceptive quality that transports the observer to a more complicated, visionary topography. The three photographs comprising Ghost City I,II,III, 2014, depicts a blurred landscape that transports the viewer in a similar manner. The images are apparently captured through the window of a passenger compartment on a moving train. From an interior perspective the pictures have a further visually manipulated “truth” that is stylistically associated with Victorian era photographs. The Ghost City images appear on first impression to embrace this Romantic photographic quality. However, the sepia tone coloration is deceiving. García-Luna does not apply a glowing look of the sepia tone at all. The golden yellow tone associated with 19th and early 20th century photography is actually derived from the discolouration of the train’s aging window glass.

The New Territories images follow a similar process of disintegrating truths. The transitory, “the becoming” inscribed within the frame of vision gives way to an implied, shifting landscape/surface from the mediated interior space occupied by the photographer. The images of wallpaper and shifting landscapes verge on the luminiferous, they virtually glow. Any form of “truth” to the photographs is nuanced to the point of identifying the effect of light with the effect of colour. García-Luna’s 21st century approach to redefining the viewing of human and natural landscapes acknowledges the continuous shift of minor illusions in her pictures (e.g., Kathgodam Express, 2014 and New Territories) likened to the familiarity of a déjà vu moment. The glimpses of a Romantic déjà vu are purposeful and enable us, the observers, to be transported. For García-Luna this shift of contemporary experience suggests “a place to be, a kind of home…that breeds a confidence and sense of ease not in relation to anything” but to her personal sense of self. 2

The photographed landscape as subject of Bridge, Kathgodam Express happens to be set in northern India, which “is specifically a place where one might not know the regionally defined guidelines of upbringing; one is outside the common interior and exterior spaces”3 The images appear to emulate this sensibility and undo the confining quality that comes with knowing too much about one’s adopted cultural setting. The images come to feel as sly and subjective as quicksilver, compressing time and space, avoiding cultural confinement, offering what García-Luna calls “less cultural construction, more nakedness”.4 This stripped bare quality is used as a starting point to guide the highly personal process of observation and interpretation. García-Luna cites the literary works of Jorge Luis Borges (1899-1986) as a recurring voice that informs her current approach to observation and the act of visual recording. Borges’ renowned narrative style developed out of an elaborate mixing of irreal narratives to address the complexities of knowledge, of knowing anything with certainty. His heady métissage of narrative sources investigates the limits of non-linear time that incorporates and normalizes both elusive past and future. García-Luna’s vision is not directly informed by a Borges narrative but plays similarly with the recording of layered realities (plural) and how meaning is rendered unstable. What links novelist and artist is the nakedness that juxtaposes “misery and common appearances, most not pretty, but also not covered with make-up and appearing to have all surfaces revealed.”5 In the series, Kathgodam Express, and in Ghost City 1,2, 3, the scratched window of a train compartment makes naked the subtle exposure of multiple overlapping picture planes that need to be negotiated by the observer, aligning the popular with the sublime. García-Luna subtly captures the physical imperfections in multiple layers of scratches and reflections in the sliding glass window of the compartment. Each layer becomes a portal of mediation to suggest exterior space exposed, removed, and largely without beauty. What emerges in her three manipulated views of ancient city “ghost” buildings is an emotional response to the enduring solidity of a city. Place matters to everyone but to better know it by name or otherwise is, again, not important, as it is left behind in the train’s journey. For the artist “it is not about beauty or the deconstruction of built form”, or about “conceptual perception.”6 García-Luna would want us to remember that with a little time or change of place and movement we might view her images again and recognize them to be stylistic ghosts of another era with no imaginative claim to being new and impactful.

II.

No one can escape from his or her own historic period and, by association, the dominant stylistic trends of the moment that impact on the photographer’s claim to documenting realities. García-Luna is, however, cognizant of

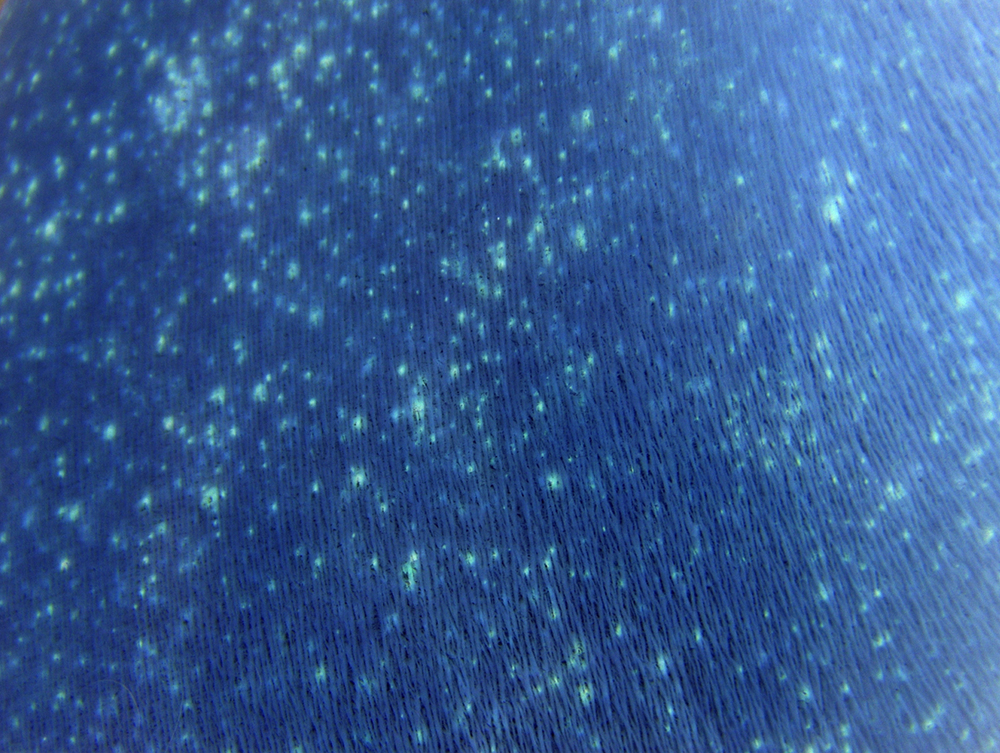

the need to leave behind the constraints of the present and shuffle the deck of stylistic strategies to better obscure that which might generally be considered representative meaning. For example, while she captures the wind-sculpted contours of a winter landscape in her recent Whitescapes (2012-13), she strategically transforms the north’s physical beauty to a point where its depicted physicality becomes of secondary importance to the observer. The realist depiction of the landscape is increasingly abstract. Rather, what triggers an emotional reaction is light itself. The traditional Canadian winter landscape of trees, horizon line of cresting snowbanks and innumerable snowy hollows recedes in the picture plane, as expected, but García-Luna’s manipulations of light sources offer to divert attention. To do so, García-Luna effectively underscores a fantastical monochromatic blue tone that shifts to white, shadowy grays, natural contrast viewers may overlook if they were physically immersed in the same winter snowscape. In the Twilight series, the shifting gradations of light grow in complexity to include a more prominent notational construction within the landscape: a metalinguistic element “written” into the picture plane. Traces of curvilinear artificial light (produced by faintly present human subjects in the photographs) are captured with the camera’s extended open shutter recording the movement of a hand-held flashlight. In the process, she manages to propose an experiential involvement with the frozen moment as a remarkable level of eloquence in image making.

The sequential images comprising Whitescapes and Twilight transform light into deep matter and permit García-Luna to suggest another reality, in the form of light as contemplative narrative writing. She, like her kindred spirit, the art photographer Duane Michals, begs the question of how a stylistic shift in the use of light as hand-written notation on the photograph (personal text by Michals, abstract “squiggles” of light by García-Luna) are linked to a personal process, the source of creativity and the illusiveness of reality itself.7 What is asked of us, as observers, is to learn to see with the eyes of our whole historic period, and not with the glaucoma gaze directed at the tiny areas bright one moment, dark the next, occasionally sliding to the left and right and out of sight in a vain attempt to capture meaning. With a patience for nature and evolving approach to abstraction, and a coherent pictorial style that asks observers to rethink the popular-sublime of landscape as something both objective and subjective, García-Luna reminds us that for the development of an open-ended process of observation we need to trust in the educative and meditative aids that each of us bring to observing pictures.

Wayne Baerwaldt,